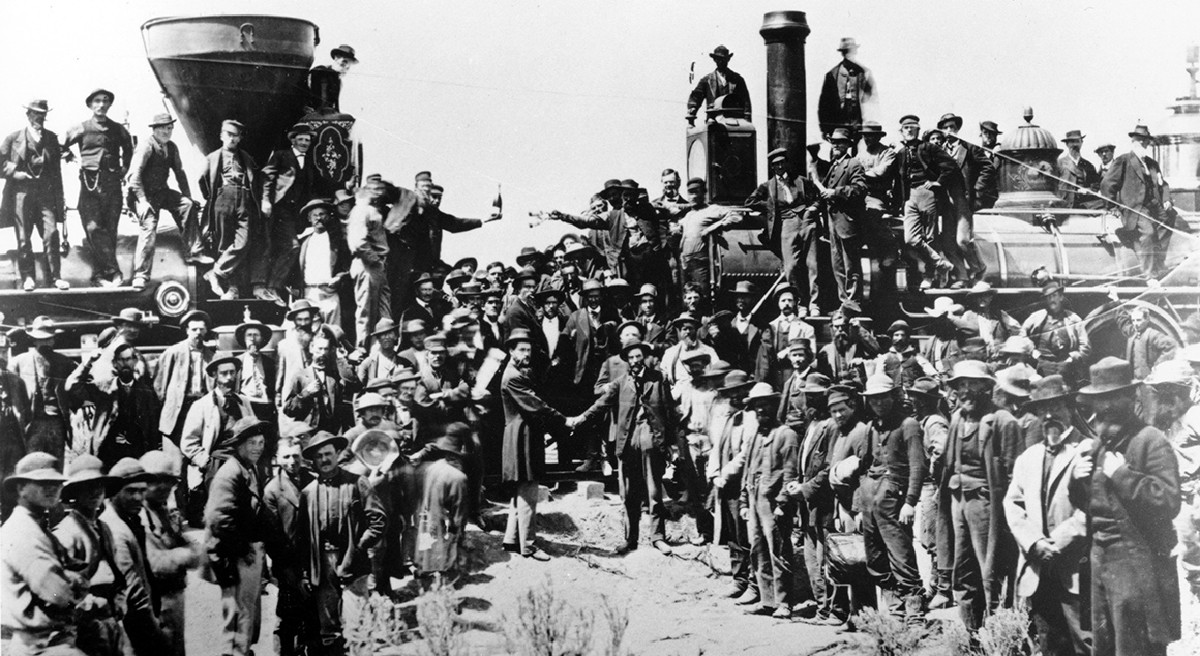

Recognize the image below? This famous photograph immortalizes the Golden Spike Ceremony at Promontory Summit, taken shortly after the joining of the first transcontinental railroad on May 10, 1869. It was perhaps the greatest engineering feat of its time, yet absent from this image are any of the 15,000 Chinese railmen who helped make it possible.

John Chinaman. Jake. Celestial. Yellow-skin. Chink. Many less-than-preferable words were used to describe the Chinese. Spat upon by many, they were however seen as invaluable to the Central Pacific tycoons who employed them. Hard-working, rarely drunk, seldom sick, paid less… Yet, despite their contributions, many of their histories are lost. When we see their faces in photographs, we see ghosts; we don’t know their names, we don’t know their stories.

One of the most notable things to keep in mind is how nativist (read: racist) forces of the era tried to paint the Chinese railmen as a coerced workforce. While there were many atrocities committed against them, the Chinese who worked for the Central Pacific Railroad weren’t slaves. They chose to leave home for work and better pay, much like immigrants do today. (Much can be said of the fact that they were paid less than the white men who did the same jobs, but the pay was still substantial compared to what they would’ve earned back home.) In true gaslighting fashion, the nativists who equated the Chinese to slaves pretended to care but really only wanted to vilify their hiring and push them out of the country.

And what of the industrialists? Leland Stanford played into the nativist sentiment when he was governor of California, but he (not surprisingly) praised the Chinese when they served him well during his tenure as the president of the Central Pacific. His mood change wasn’t unique, as the nation itself seemed to celebrate the Chinese for their work during the railroad’s completion. It wasn’t until after, when the Chinese and white former railmen went off to compete for the same jobs, did the worst of the violence take place.

A notorious example can be found in the history of Truckee, California. Once home to a healthy population of Chinese workers, the town drove them out in the 1880s using a technique of exclusion so effective it became known as “The Truckee Method.” Charles McGlashan, founder of the Truckee Anti-Chinese Boycotting Committee and the head of the local newspaper, later toured the state promoting this method. Imagine having to be his opening act.

Clearly, there’s a lot of history and nuance to uncover, but what interested me most was how the Chinese departed their predominantly rural homes for jobs in America. Many left behind bloodshed, as banditry and ethnic wars plagued the region exporting the majority of the laborers. And while we often view them as a homogenous workforce today, they were really individuals with their own reasons to leave, their own traumas and their own families left behind.

This is what inspired me to write my novel, The Bamboo Brothers. I wanted to tell a story that gives the reader a sense of what it might’ve been like to leave home, travel across the Pacific, and toil in the American West from the frigid Sierra Nevada to the deserts of Nevada and Utah. While it’s a work of fiction, all the historical elements are true.

Two brothers witness their bucolic lives in rural China upended when bandits destroy their village. Forced to flee, they enlist as railroad workers and follow an exodus of Chinese laborers to California. Thoughts of returning home accompany them as they endure the foreign and often brutal conditions of the American frontier. Little do they know that the troubles of their homeland have also emigrated to find them in the new world, splitting them apart and making them question what it means to find “home.”

At the heart of it is a coming-of-age story following the younger brother as he navigates the emotional journey of losing his family, leaving home and coming to America. It deals with the immigrant experience, family bonds and the universal struggles that none of us can escape, regardless of our skin color.